Stablecoin design — Liquidity

How to achieve stablecoin peg

Very early draft paper (not sure it will be finished)

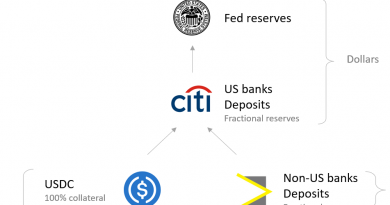

Crypto-banking 101

In my Crypto banking 101 paper, I’ve described the similarities between crypto-banking and regular banking. Stablecoin like USDC, DAI are just deposit. In turn, when you deposit DAI on Nexo, you no longer hold DAI but an on-demand IOU on DAI. Nexo will most likely not keep this DAI idle. The same is true when you deposit a one-dollar bill into your bank account.

For banking to work you need to satisfy the rules of liquidity, the ability to exercise your IOU and solvency, the ability to stay creditworthy.

In this paper, we will dig deeper into how crypto-bank should solve the liquidity constraint.

On liquidity

When you own a crypto-bank liability (DAI for MakerDAO, aDAI for Aave, your DAI deposit on Nexo) you expect to be able to get your value back when needed (on-demand).

This is why you think of your bank account as money. If you have deposited a $1 note into your bank account, you can get your $1 anytime (when the bank is open at least). The same applies to Nexo, you can deposit 1 DAI and get back 1 DAI anytime.

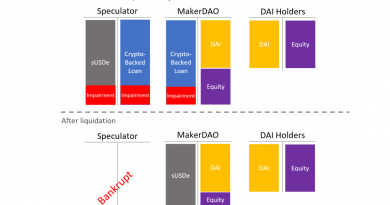

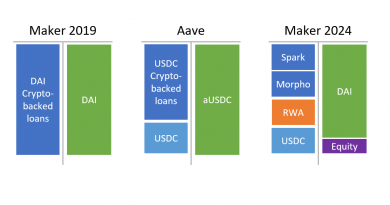

This is getting more complicated for MakerDAO. You can’t deposit $1 to get 1 DAI and do the reverse. In the original design, someone needs to take a crypto-collateralized loan to be able to create those DAI. Just like when you get a consumer loan, your bank account gets filled with money. If you want to hold DAI but don’t want to take a loan you need someone else taking such a loan and selling you DAI. But you can face a demand and supply mismatch.

The opposite exists as well. The Maker Protocol promises you $1 of assets at the shutdown nothing more. Therefore, you need to find a willing buyer of DAI.

This is why DAI was not good money last year. One type of money should be somewhat fungible with another type of money. When you transfer $100 from Citigroup to Bank Of America, $100 leaves and $100 arrive.

To become inside money, credit has to become as liquid as money. Inside money has to be convertible into outside money at par and at any time.

The End of Banking Money, Credit, and the Digital Revolution — Jonathan McMillan

The need for a risk-free arbitrage

Obviously, if you want to succeed as a stablecoin you need to be … stable, you need to feel like money. For that, you need to manage the market imbalance between the supply and demand of your stablecoin.

The best way to solve this issue is to provide a risk-free arbitrage.

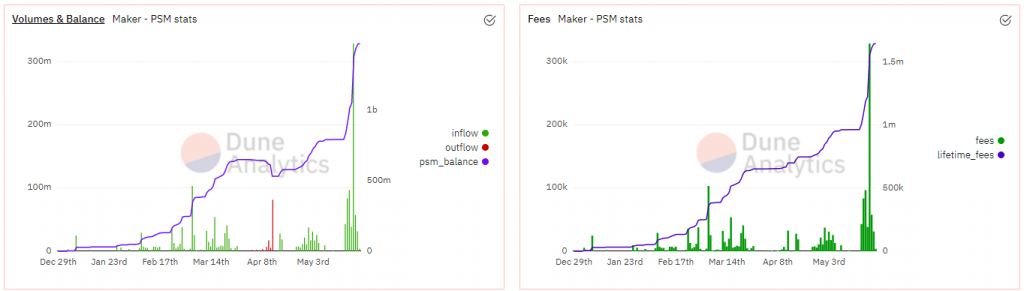

The PSM is the solution that MakerDAO implemented to provide a risk-free arbitrage. You can sell USDC to the PSM and get DAI in exchange for a 0.1% exchange fee. As you can convert between USDC and $ at par at Circle, this means that you can convert from $ to DAI. This effectively caps the DAI price to around $1.001. The opposite works as well as you can get USDC that we store in the PSM for a fee of 0.04%. The price of DAI is at least $0.9996 as long as we have some USDC stored.

The cool thing about risk-free arbitrage is that you don’t have to use the PSM to get a fair price. If the market price of DAI deviates on an exchange, someone will correct the price immediately to make a profit.

While there is still a fee, the spread is becoming quite small and DAI really feels like money.

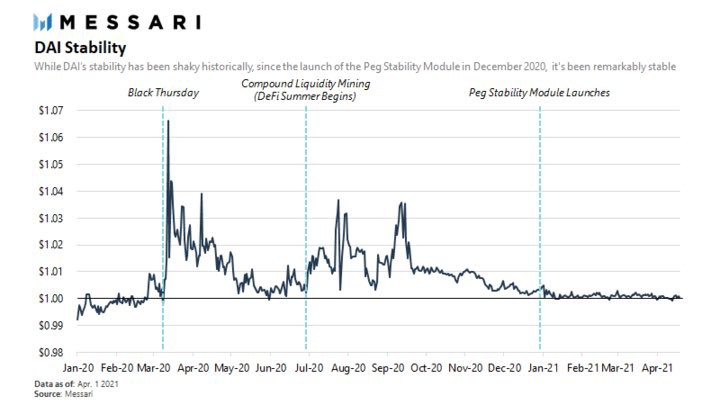

As you can see in the chart below, the PSM is used in both ways (green for USDC inflows and red for USDC outflows) and we currently have up to 600M of USDC which would provide enough liquidity for anyone to convert DAI to $. The peg is now much better and this even bring some fees (right chart).

Other protocols have found other ways to solve the peg issue. FRAX which is an algorithmic stablecoin can be created using USDC and some FXS tokens (the governance token of FRAX). The sum should be $1 + 0.3% of fees. As FXS is a liquid token, anyone can create FRAX from USDC (or ETH as the UI propose) by adding some exchange costs. The price of FXS is not relevant by itself (but some slippage can add to the cost and it doesn’t work at the extreme).

Frax provides the opposite as well. You can convert FRAX to get $0.86 USDC + $0.14 FXS for $1 of value (minus some fees). As you can convert FXS to USDC quite easily at a similar price, that gives you the full arbitrage.

Internally, Frax holds some USDC and can mint as much FXS as need to make up to $1. So it’s a risk-free arbitrage as long as the FXS conversion slippage is small. The spread is a bit wider than MakerDAO as the fees are higher and your need to handle the FXS swap fees and slippage, but the principle is the same.

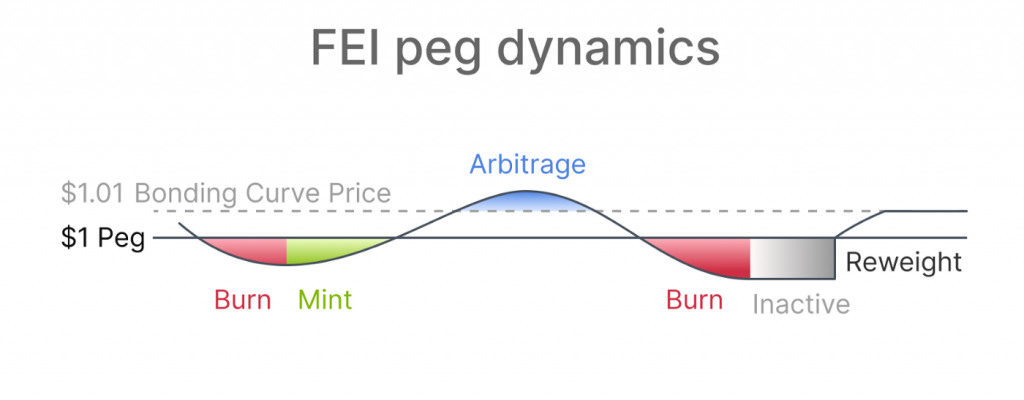

For the last example, let see the epic failure of the FEI protocol. The idea was simple, you can always mint FEI with $1.01 worth of ETH. As the protocol owns a lot of ETH (let’s assume more than liabilities), he will reweight a Uniswap pool to correct the price if it falls too much below $1.

Even with such careful attention on having a risk-free arbitrage in place, it was a mess. The reweight didn’t work as expected and FEI now trades around $0.8. The protocol has enough collateral to repay all the willing FEI holders and provide the risk-free arbitrage but their governance decided that it will not honor its debt. But it would have been possible to have a risk-free arbitrage with ETH as collateral. Converting ETH to $ is quite simple as well as ETH is quite liquid. So a $ <-> FEI risk-free arbitrage would have been possible.

As we have seen, you can find many ways to provide this risk-free arbitrage, but you need to keep something of value that is liquid. This can be called reserves or liquidity.

Obviously, holding some idle USDC is not ideal to make a profit. Hopefully, it doesn’t have to be idle.

Liquidity doesn’t have to be idle cash

A bank deposit is an on-demand liability.

Obviously, even with quite a liquid market and stable assets, when you are selling something in a rush you might lose some money. But this is a solvency issue and no longer a liquidity one.

In DeFi lending on Aave and Compound can be seen as a solution to earn a yield on the liquidity buffer. But even there, liquidity can dry up.

The Tether case

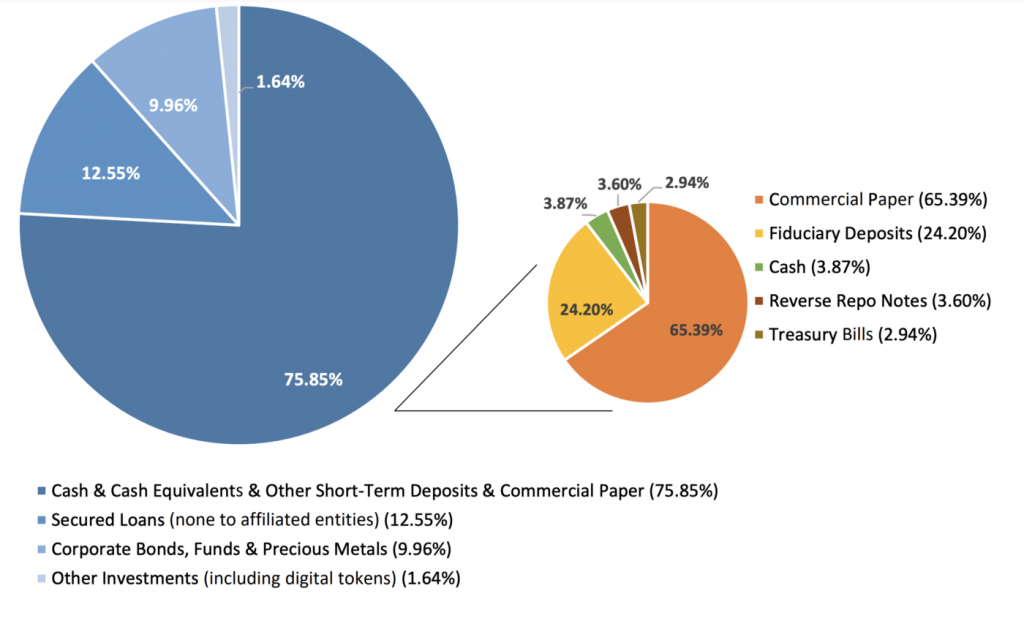

Tether (USDT) has now disclosed its holdings. The only thing that is super liquid (intraday) is cash (most likely bank account and not physical cash) and Treasury Bills (short-term loans to the US government).

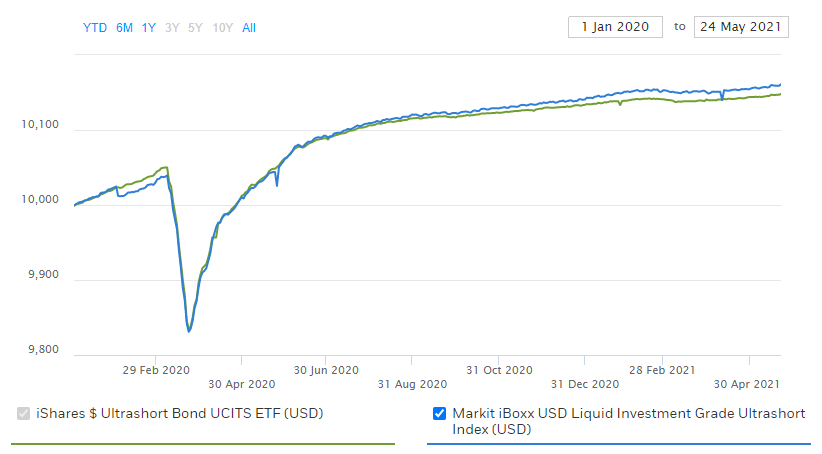

How risky is that? A good source can be ERNA and ultrashort term bonds ETF. You can see that the price is quite linear … except when it doesn’t (a 2% drop during Covid). The sharp recovery shows that the assets themselves were fine. But if you had to sell all of them during a bad period, you would have lost a few percent.

Therefore, Tether is quite sensitive to a systemic shock but you need a serious shock in the commercial paper market AND a USDT bank run to make it a reality.

How much liquidity buffer is needed?

Banks had the issue of liquidity since the beginning. The more you hold reserves, the less you can make loans that generate profit. The less you have reserves, the more you risk a bank run and defaulting on the contractual liquidity. As described by Bagehot already in 1873:

the shareholders of the Bank of England will (…) always urge their directors to diminish (as far as possible) the unproductive reserve, and to augment as far as possible their own dividend.

Bagehot, Walter. Lombard Street : a description of the money market

At this time, the Palmer rule was defined. A third of the on-demand liabilities should be kept as reserves (11% in actual cash):

In 1833 Horsley Palmer, the governor of the Bank of England, had adopted a rule: against all ‘liabilities to pay on demand’ (i.e. banknotes issued and deposits, which could be withdrawn without notice), the bank should keep a reserve of a third of the total value; two-thirds of this should be in securities such as government stock, and one-third in bullion (gold and silver).

The Rise and Fall of the City of Money — Ray Perman

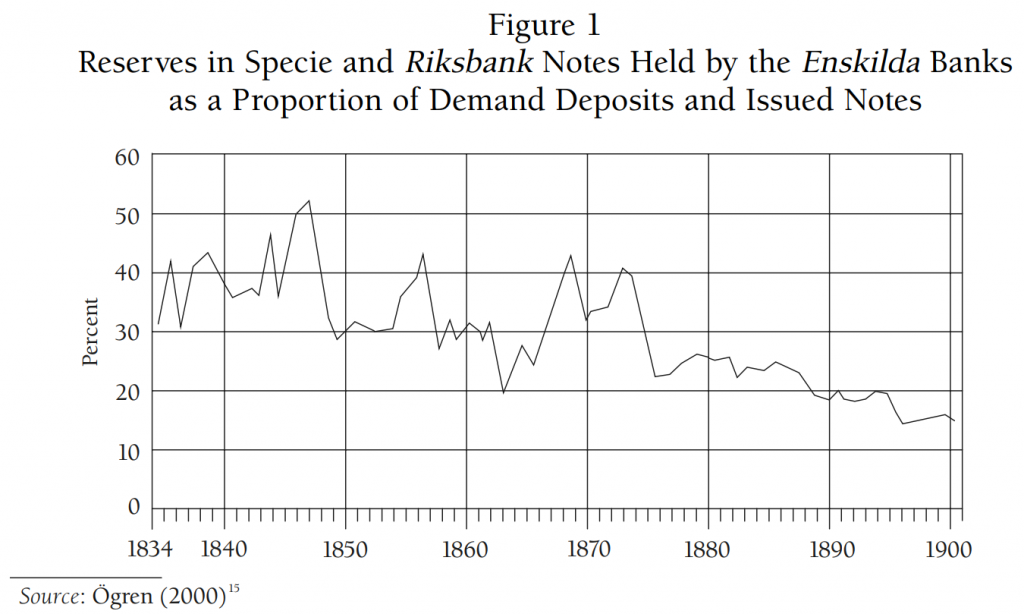

Looking at the free banking era in Sweden, it seems that the Palmer rule was used initially then the reserve/liquidity ratio was decreased over time.

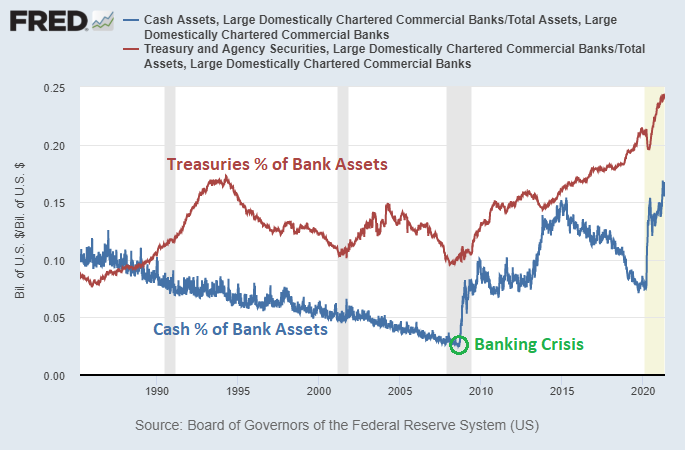

If we turn to modern US banks, we can see that the amount of cash on hand was decreasing until the banking crisis (with a bank run). This means that even with FDIC insurance and strong regulation, you still need to have significant reserves (around 15% currently).

It is therefore difficult to find what is the proper size of such a liquidity buffer. It obviously depends on the stability of your deposit accounts/stablecoins holders and the maturity of the rest of your assets.

Nevertheless, if 5% cash is not enough for the real world, probably something between 10–20% is more appropriate for the crypto world where things are moving faster.