Lending and stablecoins

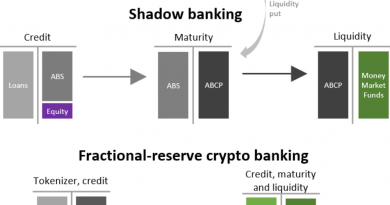

DeFi stablecoin issuers have long had a symbiotic relationship with lending activities. In this article, we explore the intrinsic connections between lending protocols and stablecoin issuers. Stablecoins not only originated from lending protocols, but lending protocols themselves can be seen as a type of stablecoin issuer. Additionally, there is a growing trend to delegate the lending functions of stablecoin issuers to specialized lending protocols. We conclude with an initial discussion on the types of stablecoins that stablecoin issuers should lend.

Stablecoins started as lending protocols

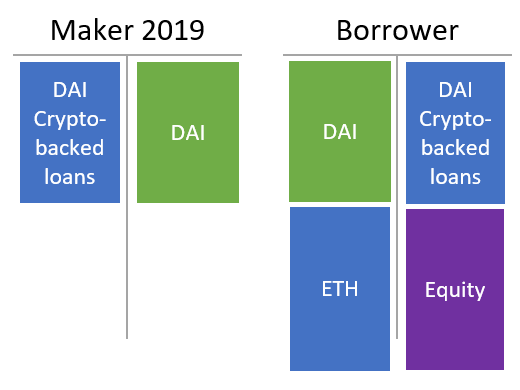

What was MakerDAO originally, if not a lending protocol designed to borrow DAI (the stablecoin) against ETH as collateral?

Let’s step back and start with a bit of formalization (more on that in the accounting primer). We define a stablecoin issuer as an entity with a balance sheet that issues stablecoins as liabilities, with a promise to keep them around par (relative to USD here). DAI also promises redeemability during an emergency shutdown. For more on the stabilization of DAI, refer to the article The history of a DAI at par value.

To maintain a balanced balance sheet, the issuance of a stablecoin requires a corresponding increase on the asset side, typically in the form of collateral backing the stablecoin. For now, we exclude equity from the discussion, but it’s important that a stablecoin issuer does not have negative equity, i.e., it should not be insolvent. This increase on the asset side represents the loan taken by the borrower, which initially matches the value of the minted stablecoin. Note that the collateral does not appear on the balance sheet since ownership is not transferred—only control. Over time, assuming an interest rate on the loan, the loan’s value will increase while the minted stablecoin remains constant. This difference constitutes profit for the stablecoin issuer.

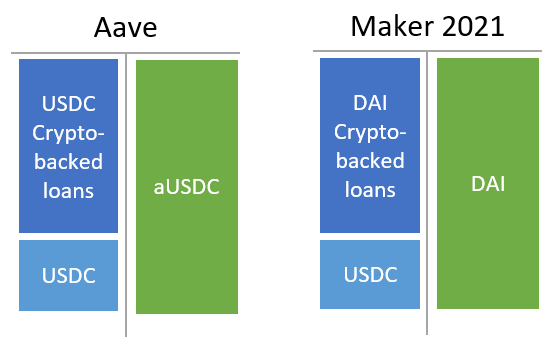

Lending protocols are stablecoins issuers

Let’s now turn to lending protocols and argue that they are, in fact, a specific type of stablecoin issuer. The key is to recognize that these stablecoins are not marketed as such.

In the diagram below, we compare Maker’s balance sheet after the inclusion of the PSM (USDC) to Aave’s balance sheet, limited to the USDC market. Surprisingly, there are no significant differences. Both aUSDC and DAI can be redeemed for USDC at par. While all aUSDC accrue value through rebasing, only DAI deposited in the DSR accrue interest (though, in theory, all DAI should be deposited). While Aave issues loans in USDC, Maker extends loans in DAI.

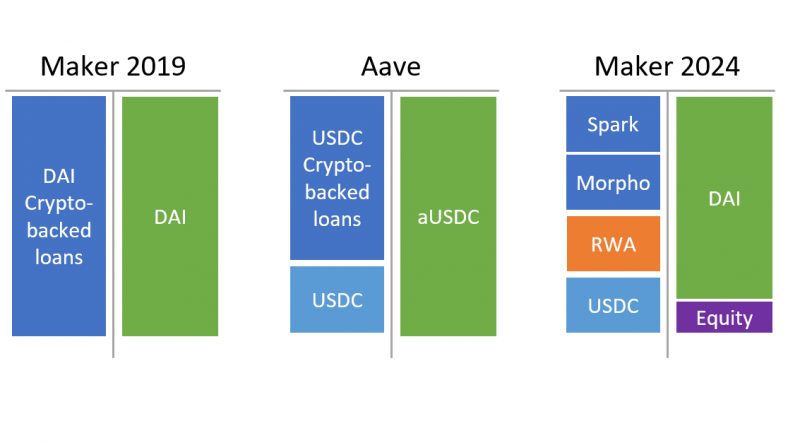

Stablecoins externalizing the lending part

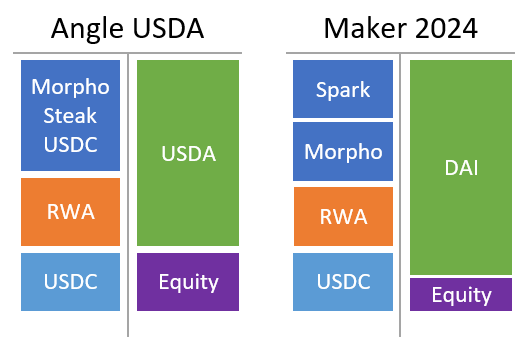

As lending protocols have become more specialized and established, it has started to make sense for stablecoin issuers to delegate this component. For instance, Angle USDA uses Morpho as its lending component, even though the team has developed a cutting-edge lending system themselves. Similarly, Maker now primarily relies on Spark (an Aave v3 clone) and Morpho for its lending needs, replacing the traditional vault system.

There are several reasons for this shift. First, distribution is crucial for finding borrowers. Leveraging a well-known protocol helps attract borrowers where they already are. Second, aggregation improves liquidity. For example, Angle USDA has $15 million invested in steakUSDC (Morpho’s lending vault). Pooled with other lenders, the instant liquidity is currently $23 million. This means that in the event of a bank run on Angle USDA, all investments in steakUSDC can be unwound in a single block. This would not be possible with a proprietary lending system, where the typical solution is to increase rates to disincentivize borrowers (or wait until they get liquidated). Third, delegating the lending function allows stablecoin issuers to focus on higher-level considerations, mainly Asset Liability Management

Lending yes, but in which stablecoin

As we have seen, the lending of assets by stablecoin issuers is increasingly outsourced to dedicated lending protocols. A key question remains: which stablecoin should be lent out? Should it be the native stablecoin issued (such as DAI or USDA), or the stablecoin used to stabilize the peg (like USDC, i.e., higher-level money in the hierarchy of money)?

The naïve answer is to use the native stablecoin. For some stablecoin issuers, such as Liquity v1, this is the only valid answer. But more broardly, two reasons:

- A stablecoin issuer can always mint its stablecoin.

- As long as it is not borrowed by a user, such a minted stablecoin has no cost (neither in terms of capital nor liquidity/peg).

The second point is crucial. It is often wrongly mentioned that a stablecoin issuers doesn’t have a cost of capital. Misunderstanding this can lead to stablecoin issuers advertising drastically low borrowing costs as an incentive to use the stablecoin. However, since borrowers will generally sell the stablecoin, the net effect is a reduction in revenues (resulting in less to distribute to organic stablecoin holders). This approach is not recommended.

Nevertheless, lending in its own stablecoin could be done at a lower rate, as non-borrowed USDC in the lending protocol will act as a drag on lender performance. If liquidity in the lending protocol is 10%, using its own stablecoin could decrease the borrowing rate by 10%. However, this is not without cost. Idle USDC in the lending protocol provides liquidity reserves that are unavailable if you use your own stablecoin. Moreover, using your own stablecoin reduces the aggregation benefits discussed in the previous section. Therefore, the best strategy is still unclear and the difference is subtle. It should be determined on a case-by-case basis.

In conclusion, it is important to recognize that lending protocols are a subset of stablecoin issuers. The specialization of lending protocols and the delegation of lending functions to these protocols are leading to changes in the market structure. We can expect stablecoin issuers to increasingly become the primary lenders on these lending platforms.