Crypto Banking 101

This paper describes the business of banking and how it applies in the crypto-world. While Decentralized Finance is all about reinventing the wheel and experimenting (e.g. algorithmic stablecoins), banking is an old industry and rules still apply.

Links for more in-depth research:

- The Crypto Banking System

- Stablecoin design — Liquidity

- How to fix the par value of stablecoins

- The history of DAI at par value

- Introducing ClearingDAO — A decentralized clearinghouse for stablecoins

- Crypto-banking differences with traditional and shadow banking

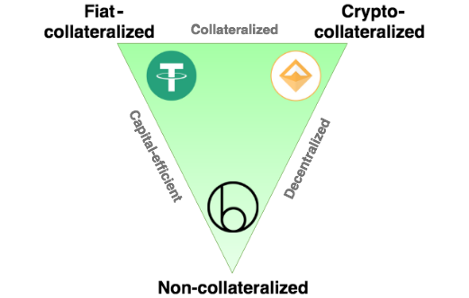

The first classification was done by Haseeb Qureshi in his article Stablecoins: designing a price-stable cryptocurrency (2018). The term stablecoin means being stable regarding another asset, usually the US Dollar (USD). Stablecoins are defined by being either fiat-backed (with USD in a bank account), crypto-collateralized (using USD denominated loans backed by a greater value of crypto-assets), and non-collateralized or algorithmics (backed by nothing).

This classification is still the most used today. In this paper, we will step back and take a banking view of money and how that can apply to crypto. We will start by looking at the money layers (in real-life as in crypto), the business of banking, the constraints (solvency and liquidity) and use this framework to look at the banking space in crypto.

Banking layers

While a $1 bill looks similar to a $1 bank deposit but they are far from being the same. This section is about the hierarchy of money. You can learn more by following the master class of Perry Mehrling, Economics of Money and Banking, or reading the book Layered Money: From Gold and Dollars to Bitcoin and Central Bank Digital Currencies.

At the top, there is usually a commodity (like gold, synthetic commodity (like Bitcoin), or a fiat currency (like USD after Gold Standard. From there, many layers are developed, either for convenience (a Banknote is better to buy a coffee than gold) or by the government authority (like the Bank of Amsterdam limiting the use of coins).

The hierarchy of money

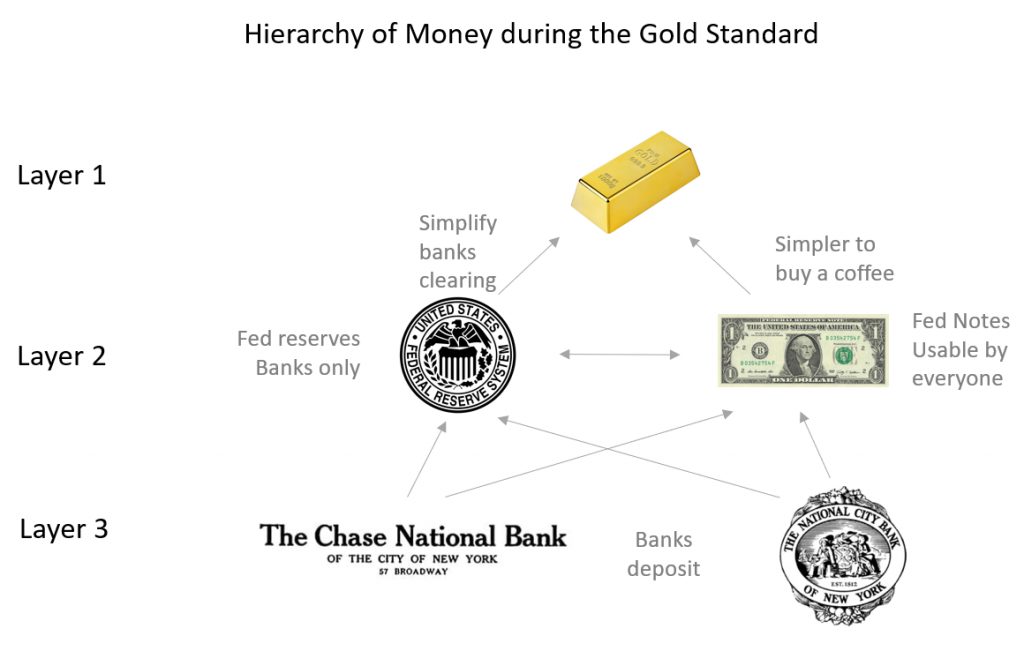

Let’s take a simple case, the US system during the Gold Standard (after the instauration of the Fed so around 1920). It was a 3-layer system. At the top, you would have gold. Quite secure but difficult to transact with.

Just below you would have the Federal Reserve System issuing two kinds of promises (IOU) to pay gold. The first one takes the form of the Federal Reserve Note, which is the piece of paper you use every day (or less if you are a digital native). Under the Gold Standard Act, it was a promise to pay gold at an exchange rate of $20.67 per Troy ounce.

Bank would take Federal Reserve Notes and give you bank deposits. This was a layer 3 money. The bank made a promise to give you Federal Reserve Notes for your deposit on demand.

To simplify the movement of money between banks, it made sense for them to just keep a ledger at the Fed. No need to transfer gold or Federal Reserve Notes between them every day, just a new line in the ledger.

All those elements would be called money. But it’s only when your bank becomes insolvent or when your country leaves the Gold Standard that you find that layer 1 money is the best and only true money.

Those days, gold is no longer there, the layer 2 became layer 1. But the story remains the same.

The hierarchy of Bitcoin

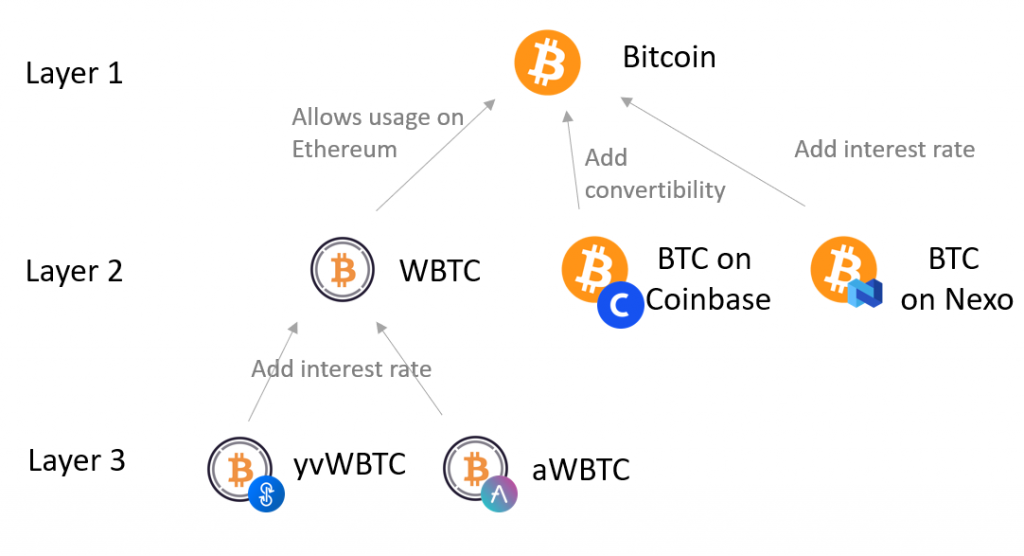

The same kind of hierarchy also exists with Bitcoin. At the top is BTC, the currency of the Bitcoin network, this is layer 1 and the top of the pyramid.

On layer 2, you have BTC hold on exchanges (like Coinbase). You don’t directly hold the bitcoin on exchanges, what you have is an IOU of bitcoins. As the saying goes not your keys, not your coins. Nevertheless, having your BTC on an exchange adds easy convertibility to other currencies. Exchanges are expected to hold your BTC and not play with them. Kraken, for instance, provides a proof of reserves. This is full reserve banking.

Also on layer 2, you have BTC on lending platforms (like Nexo or BlockFi). In this case, you know that the lending platform is keeping all your BTC on its balance sheet. Some are lent to third parties in the exchange for a yield. They use fractional reserve banking, i.e. they don’t own enough BTC to cover all the IOU issued. If you deposit 1 BTC, the lending platform owes you 1 BTC on-demand no matter what happens. They can, and will, do whatever they want with the BTC like loaning it.

The last element on layer 2 is Wrapped BTC (WBTC). This is a protocol that transfers BTC on the Ethereum network. This open usage of BTC on DeFi and unlock layer 3. If you deposit your WBTC on Yearn or Aave, this WBTC is used by the protocol and you get an IOU with an interest rate. On Aave, you can get your WBTC on demand (most of the time). Some of the WBTC is lent to other customers for a fee (and with the security of another crypto-collateral). Aave even has a Safety Module to compensate people in case there is a loss somewhere. This is again fractional-reserve banking.

Fractionally reserved, liability-issuing entities will exist, and the market will price each form of second-layer BTC with an according interest rate.

— Bhatia, Nik. Layered Money: From Gold and Dollars to Bitcoin and Central Bank

The hierarchy of money, eurodollars, and cryptodollars

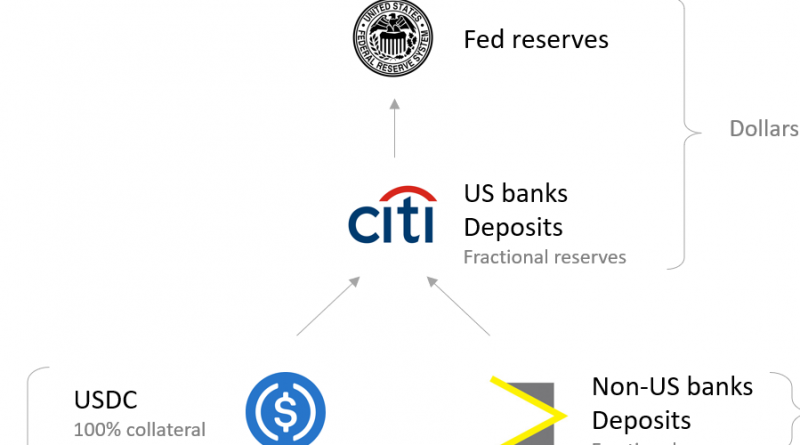

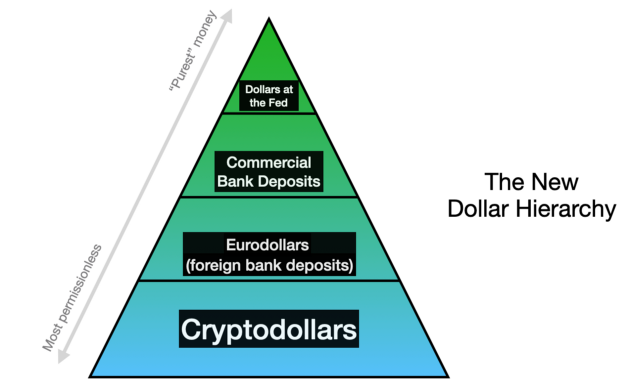

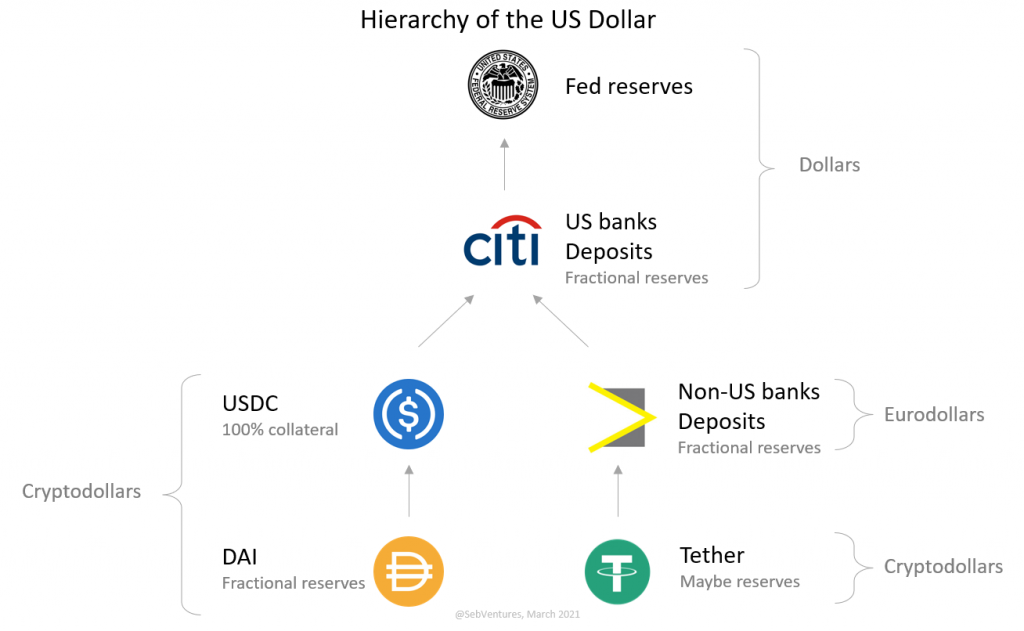

Coming back to the US, let refine the model and update it for the year 2021. We still have the Fed reserves on top (remember gold is no longer used) and US banks deposits like Citigroup. Let’s remove the Fed notes because who uses paper cash anyway?

We can add two new types of dollars. The first one is the eurodollars. It represents all bank deposits from banks that don’t have access to the Fed (i.e. all banks or branches outside of the US). Created after WWII, it’s interesting to note that its growth is due to regulatory arbitrage. Initially, some countries didn’t want to have their accounts frozen by the US. Using a foreign bank as a proxy, they were safer. More lately, the eurodollar market boomed due to less regulation. The market is now as big as the dollar market and you can open a Eurodollar account in the US.

In the same sense, cryptodollars are dollars that are on the blockchain. A stablecoin like USDC is backed by an equal amount of dollars in a US bank account but the coin itself is outside of the US bank regulation. Tether is built on the same model except it uses eurodollars as backing because no US bank wants to serve them. While they claim to be transparent and 100% backed, it’s considered shady. Finally, MakerDAO issue the DAI stablecoin that can be redeemed for USDC (with 22% of USDC reserves currently).

This presentation is not very far from the last article of Haseeb Qureshi on the subject Fighting to be STABLE: the Evolution of Stablecoins but we reorder some elements and remove the permissionless scale.

At this stage, we have defined that banks add a layer on top of the base currency to provide services to their clients (easier to use or interest generating). But how are they making money?

The Business of Banking

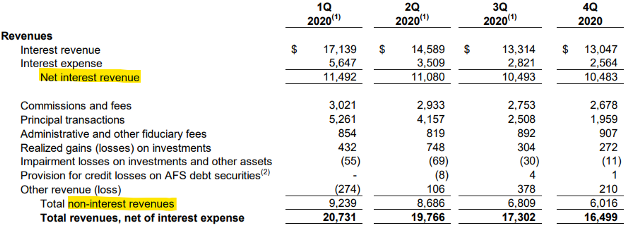

Banks need revenues to pay for expenses and shareholders. They get those from two sources: interest revenues and non-interest revenues.

Non-interest revenues a.k.a. fees

The simplest way to earn money is to sell the layered money as a service. For my corporate bank account, I pay every month the privilege to store money in their systems and have the ability to receive and emit transfers. For WBTC, Coinlist, one of the WBTC merchants, charges 0.25% to convert BTC to WBTC. Coinbase Custody will charge you 0.50% annually to safely store your BTC (and give you an IOU, i.e. layer 2 money).

This is more a service revenue than a banking revenue. For institutions that just keep custody of the asset on which they issue an IOU, that’s the only way to make money.

Net interest revenues

The core of banking is behind the net interest revenues. When you deposit cash in your bank account, the bank might offer you a 1% interest rate. This is an interest expense for the bank (they pay you). The cash will then be lent to another client at a 3% interest rate. This is an interest revenue for the bank.

The net interest revenue is the difference between interest revenues and interest expenses.

The spread between the two interest rates is the bread and butter of banking. In a competitive market and without regulation distorting the market, the only way to create this spread is to take some risks. The most two commons ones are:

- credit risk: the risk that the borrower doesn’t repay

- interest rate risk: if you lend for more than one day, the risk that the market interest rate change

In crypto, there are two important ones:

- liquidation risk: loans are overcollateralized but you expect to be able to liquidate the collateral to avoid any losses.

- protocol risk: the blockchain is code, and code might be exploited leading to losses.

Full reserve banks are not taking those risks. Kraken Bank, for instance, is a full-reserve bank. Same for Circle that provides USDC.

Kraken Bank, as a bank, is required by Wyoming law to maintain 100% reserves of its deposits of fiat currency at all times. If every client were to demand withdrawals of their fiat at the same moment, Kraken Bank would be able to fulfill each withdrawal immediately without regard to how many loans we had outstanding. — Kraken Blog

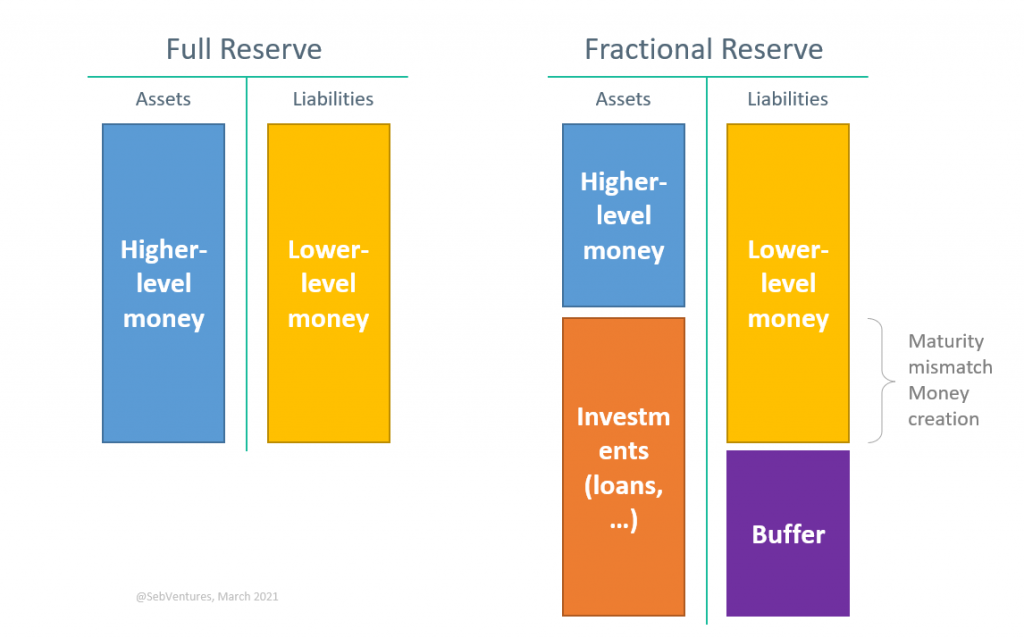

Banks on fractional reserve are making a credit transformation. They borrow short term (demand deposits) and lend long term (housing loans). This maturity mismatch is what creates money. You lend quite safely to a bank (usually with state insurance) and they lend to small businesses that might default. This creates an interest spread, i.e. profits.

Obviously, there is a reason why banks are not reckless. They have constraints and could endure severe consequences if they fail.

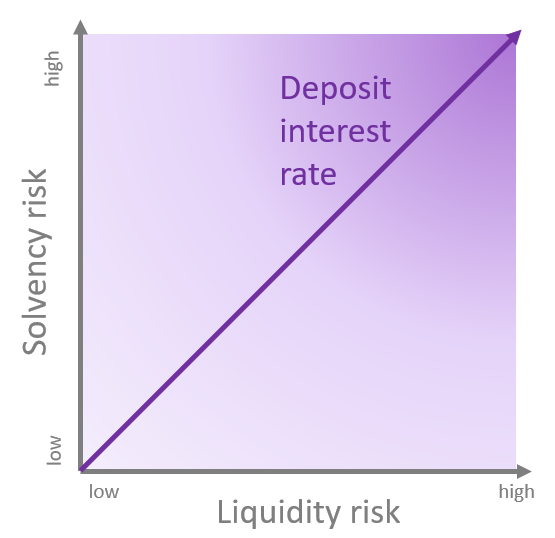

Banking constraints

Banks have constraints that limit their ability to lend too much and to take too much risk. Those are solvency, i.e. having enough assets to cover the liabilities, and liquidity, i.e. giving the ability to convert lower level money to the higher level money at all times (e.g. USDC to a bank deposit or a bank deposit to cash). Both are related to the balance sheet of the bank.

Solvency

The first constraint is solvency which represents the ability of the bank to meets its financial obligations. If a bank has $2B of assets but has issued $3B of bank deposits, you know there is a problem. The first $2B that withdraws might get something but there will be nothing left for the late ones. By simple game theory, everyone will withdraw and the system will collapse.

This is a problem most algorithmic stablecoin faces (like ESD, DSD, Basis). You can be creative by adding assets like “faith”, “future cashflows”, but that leads us to the second part of the solvency constraint.

Another component of the solvency constraint is the quality of the assets. If you back your bank deposits by shady investment, depositors will find it a bit risky. You might be solvent today, but what about tomorrow? If the assets are somewhat risky, you might feel safer if the bank is also providing a buffer in case the value of the assets decreases. This is the equity part for banks (or the surplus buffer in the MakerDAO case).

Usually, there are two brackets. You might use full-reserve banking and don’t take any risk with your bank deposits. In such a case, you don’t really need a significant buffer. Most fiat-backed stablecoins are in this case. In theory, it would mean USDC-backing would only be US bank deposits (the money layer above). In practice, safe assets like T-Bills or term deposits seem considered fine as well.

In case you are on fractional-reserve banking, things are a bit complex. When you deposit your cash on a bank deposit, you don’t want to read all balance sheets to check which one seems safe and which one isn’t. In most (all?) countries the regulator will apply rules to level the playing field. The regulations are based on Basel iii which defines the size of the surplus that a bank should keep for operating.

Liquidity

Liquidity can be defined as the amount of lower-level money liabilities divided by the amount of higher-level money assets. If this ratio is below one, it might not be possible for all clients to withdraw their deposits at the same time. Not that the bank is insolvent, but it just doesn’t have the high-level money needed at hand. You might need to wait to get your high-level money.

Banks regulations, e.g. Basel iii, use the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) to define how much high-level money the bank should keep. There is one assumption that defies the odds (in crypto at least): bank deposits are considered as long-term capital. This makes sense in the real-world. People don’t withdraw all their money at the same time. In a crypto-world full of people that call themselves degenerates and are ready to flip billions in a day to farm the next protocol? Not so sure.

This is one reason Nexo introduced term deposits as a way to be sure liquidity will not evaporate in a day. You are incentivized to lock your capital for up to one year. That will make sure that liquidity doesn’t evaporate when it’s needed.

Implications for crypto-banks

In the real world, the difference between banks for deposits is quite thin. Regulations create homogeneity. This isn’t the case in the crypto-world. You can use full-reserve banks (Paxos, Circle) and fractional-reserves banks (MakerDAO, Nexo).

Different banks can have different policies, some more aggressive, some more conservative. Some would be fractional reserve while others may be 100% Bitcoin backed. Interest rates may vary. Cash from some banks may trade at a discount to that from others. — Hal Finney, 2010

As we have seen, each bank has one goal: increasing the volume of bank deposits so they can collect the spread between funding rate and investment rate and others fees.

You can compete on marketing/brand, payment rails, … but the main factor will be the interest rate provided to depositors. If your lower-level money is riskier than the competition you might pay a bigger interest to your depositors to keep them happy. This is why a deposit at Nexo gives you yield and not at Coinbase. You don’t earn interest by having USDC but you can by using DAI (using the DSR or Chai). Remember, using a money market like Aave is different as it would give you lower-level money (aDAI instead of DAI) with more risk (but more reward).

For crypto-banks the question is, therefore, the following:

How do you manage your balance sheet to meet the constraint of solvency and liquidity while optimizing the spread between funding and investment rate?

The winner will be a trillion-dollar company.